I read Yann Martel’s popular, highly praised, Booker-winning novel, Life of Pi earlier, and I liked it a lot. However, there was one small detail in Life of Pi I could never quite forgive or forget: a character in the novel claims that I will surely become a believer in God after reading Pi’s story, if I haven’t been a believer so far. Well, I considered this claim a bit presumptuous to begin with, and sure enough, I didn’t become a religious person just by reading the novel. Life of Pi is a good book, one I recall often and with pleasure, and Pi himself is one of the most likeable protagonists I’ve come across in a long-long time – and still, it continues to bother me that the novel tried to interpret itself for me, told me in advance what I would (or should) feel by the time I got to the end, and then it failed to create the impression it promised so vehemently.

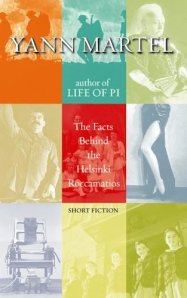

Anyway, I wasn’t at all set against Yann Martel, and I was planning to read this slim collection of stories ever since a good acquaintance of mine wrote a highly favorable review of it. Helsinki contains four early stories by Yann Martel. The title story is about the last months of a young university student dying in AIDS; the second story, ‘The Time I Heard the Private Donald J. Rankin String Concerto with One Discordant Violin, by the American Composer John Morton’, deals with the wonderful, unique, life-changing and life-preserving effect of music and art in general; ‘Manners of Dying’ tells the story of the last night and execution of a young man sentenced to death in several different versions; while ‘The Vita Æterna Mirror Company: Mirrors to Last till Kingdom Come’ mostly deals with the importance of remembering and the preservation of the past.

I consider all four stories good, but let me add that the title story is such a simple, honest, heart-wrenching work of art, devoid of any kind of melodrama and kitsch that I would have forgiven Martel quite a lot after this story. As it happened, I didn’t have anything to forgive him for because the other short stories are good as well. True, they are not as good as Helsinki, but they are way better, more authentic and more clever than a whole lot of short stories I encountered in my life which I read in ten minutes and then forgot in five.

As I was writing this entry, I tried to find some points of connection among the four short stories, and perhaps it’s not taking it too far to say that each of the four stories deals at least partly with the way memories, art and stories in general help to understand life and/or make it more bearable even when one is already touched by the shadow of death.

Although when I was reading these short stories, it never occurred to me to compare them to Life of Pi – which is without a doubt a more well-structured, more mature book – , as the two books seemed so different from each other, after some time I realized that there is a lot in common in these two books, and in fact, Life of Pi is exactly about that saving effect of art which I mentioned in the previous paragraph in connection with Helsinki.

Of course it’s quite obvious from the stories in this collection that they were written by quite a young man, and they often seem somewhat immature, so it’s not surprising that this book didn’t kindle too much interest before Martel won the Booker with Life of Pi. But I’m really pleased that Life of Pi became a popular and successful novel, as it taught me the name of Yann Martel and in a way made it possible for me to read these early stories as well – stories I appreciate more than Life of Pi. The short stories in Helsinki doesn’t tell me what I should feel during or after reading, and they don’t promise me such things that my belief, world view, or anything will undergo an unprecedented change if I read them. They are simply good stories which affect me, and evoke strong emotions in me – emotions I won’t air and analyze on this blog.